Can The Number Of Supreme Court Justices Be Changed

A version of this Voter Vital was beginning published on March 2, 2020. Information technology was updated on September 22, 2020.

The Vitals

The expiry of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and President Trump'south determination to put a successor in place quickly has focused new attention on the Supreme Court. In recent presidential campaigns, Republicans more than Democrats have fabricated selecting federal judges, peculiarly Supreme Court justices, a top event. Some Democrats are talking most enlarging the courtroom if the Senate confirms a Trump nominee and Democrats accept control of the White House and both legislative chambers. Earlier in the campaign, some Democratic candidates proposed changes to the size of the Supreme Court and the tenure of its members.

Congress hasn't inverse the court's size—nine justices—since the mid-19th century. The justices, like nearly half the roughly 2,000 federal judges, have tenure during what the Constitution calls "good Behaviour"—essentially for as long as they want to serve, subject only to rare legislative impeachments and removals. Unsettled is whether Congress could limit justices' tenureon the Supreme Courtroomas long as it preserves their tenure as judges by reassigning them to other federal courts.

-

It typically takes a crisis to generate support for major change to the federal courts, but some Democrats have vowed to push the event if Trump fills RBG's seat after Republicans blocked Obama'southward nominee in 2016.

-

The Constitution specifies no size for the Supreme Courtroom. Congress settled on 9 in the late 1860s to match the number of judicial circuits.

-

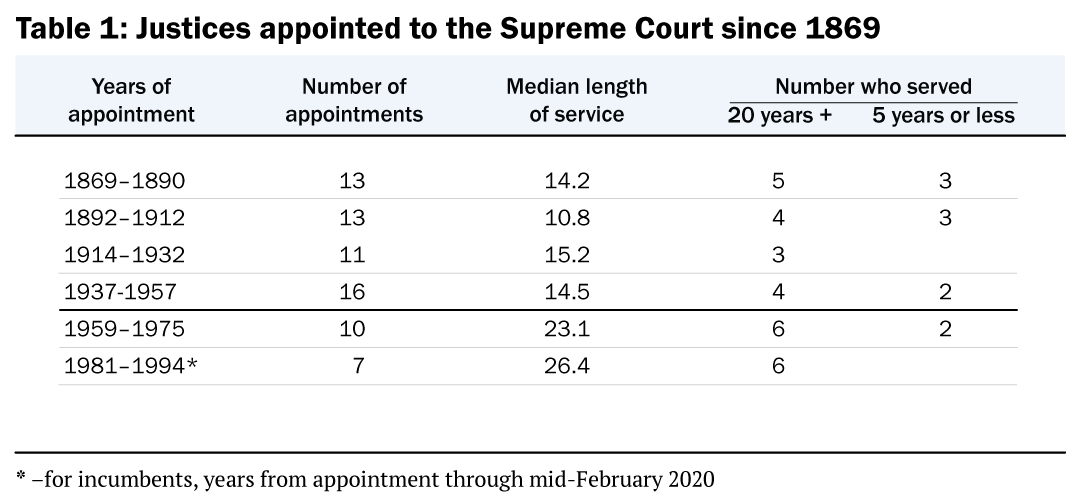

Supreme Court justices accept been serving longer terms, with a median term length of about 26 years since 1981.

A Closer Look

A review of competing proposals

Interest groups and candidates offer both partisan and non-partisan proposals.

Adding Seats every bit Payback:

In the partisan approach, Democrats—once they are in control of the White House and Congress—would enact a statute adding two seats to the court, whose Democratic appointees would counter the most recent Republican appointees. Onetime Attorney Full general Eric Holder raised the prospect in March 2019, every bit did progressive groups such every bit Take Back the Court and Demand Justice .

Advocates are frank virtually their motives. Republicans, they say, stole a courtroom seat from the Democrats in 2016 when they refused to consider Merrick Garland, Obama'due south nominee to supervene upon the late Antonin Scalia, and so in 2017 filled the vacancy with Neil Gorsuch on a political party-line vote. Add together-seat advocates also point to Brett Kavanaugh'due south controversial confirmation amidst claims that neither the Justice Section nor the Senate fully investigated charges of misbehavior from his loftier school days and beyond.

More broadly, critics note that presidents who came to part despite losing the popular vote (Trump, decidedly) appointed four of today's five bourgeois justices – and Senate confirmation of RBG's successor would make it one more than. And while senators historically have confirmed justices past margins big enough to represent a majority of voters even given the Senate's constitutional malapportionment, the senators who confirmed Justices Clarence Thomas, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh represented less than half the population. A court so constituted would arguably face a legitimacy crisis were it to commencement overturning legislation enacted by a popularly elected Democratic president and Congress. (I offered that analysis hither, while rejecting current calls to increase the court'southward membership.)

A Supreme Court of 15 justices

Other proposals have at to the lowest degree a veneer of nonpartisanship. They reflect an attitude of "do something" about the court brusque of a partisan restructuring. Former Southward Curve Mayor Pete Buttigieg, a contender for the Democratic nomination in 2020, proposed a Supreme Courtroom of 15 justices. Borrowing from a draft law review article, he suggests x justices divided equally betwixt those "affiliated with" i or the other of ii major parties; those 10 would select five more. That arrangement, he claimed in the October Democratic debate, would "depoliticize the courtroom," adding that "Nosotros can't go on similar this, where every single time at that place is a vacancy, we have this apocalyptic ideological firefight over what to exercise next." (The same draft law review article as well proposed a rotating nine-member court drawn by lot from the 170 or so court of appeals judges, simply this proposal has received little attending.)

Time limits on justices

More than common nonpartisan proposals would impose term limits on justices. A bipartisan grouping of judges and law professors began to push button this idea in 2009, and long-fourth dimension and highly regarded political analyst Norman Ornstein has promoted it at to the lowest degree since 2014 and renews the call regularly.

Proponents propose an 18-year term followed past, if the justice wishes, service on a lower court to honor the ramble hope of adept-beliefs tenure. Fully implemented, that arrangement would produce a Supreme Court vacancy every two years (barring unanticipated openings). That, say advocates, would lower the temperature of confirmation battles. Both sides would realize that the nominee would not be on the Court for the quarter century or more that has become the norm. What'southward more, regular turnover would deter the search for young, less-experienced nominees who might serve 2 or more decades, and information technology would bring new blood more often to an institution that was created when average life spans were much shorter than now.

Major questions

Is there any appetite for changing the Supreme Court?

Information technology typically takes a crisis to generate support for major change to the federal courts. Until now in that location has been little show today of public ambition for such change, but the rush to fill RBG's seat late in the election year appears to have whetted the appetite. The size of the Supreme Courtroom came up, albeit obliquely, in the 2019 Democratic debates, in particular during the 12-candidate October debate, and the commentariat occasionally raises the affair. Several Autonomous senators in a Supreme Court cursory pointed to a May 2019 Quinnipiac University national survey that they claimed showed "a bulk now believes the 'Supreme Court should be restructured in order to reduce the influence of politics.'" But the survey question gave no definition of "restructured" and supporters registered just a bare bulk. A Marquette Academy Police force School national survey in October 2019 besides included a long banking company of questions about the court. Most relevant, information technology establish that about three-fifths opposed "increase[ing] the number of justices," and that fifty-fifty among committed Democrats (as opposed to "Lean Autonomous"), support was evenly divide. By contrast, most three-quarters favored term limits regardless of party.

As the presidential campaign kicks into higher gear—and with the courtroom now hearing arguments and eventually issuing decisions on polarizing problems such equally transgender rights in employment and the fate of non-citizens brought to the state every bit children—proposals to overstate the court or trim its members' tenure might gain traction and move the campaign beyond Republican boasts about filling vacancies and Democratic pledges to appointRoe-sympathetic justices.

Would enlarging the Supreme Court produce quid pro quos?

Adding seats to the courtroom could precipitate a game of tit-for-tat. Upon gaining command, ane political party would aggrandize the court, and after the next election, the other political party would slim it back down to size or enlarge it even more than. Such "rinse and echo" politics would exist costly for the court, creating if nothing else, full employment for the court'south carpentry shop as it reconfigured the court's bench every few years.

Is anything sacrosanct nigh a nine-seat Supreme Court?

The Constitution specifies no size for the Supreme Courtroom, which has varied from five to 10 justices, depending on the number of judicial circuits. A major job of Supreme Courtroom justices until the late nineteenth century was to travel near their assigned circuits, trying cases in the quondam circuit courts, the system'due south major trial court until 1891. Congress settled on nine circuits in the tardily 1860s and thus nine justices.

Despite this nine-by-happenstance, some speak of a nine-fellow member court as a Goldilocks ideal—non too big, non too minor. In opposing Franklin Roosevelt'due south 1937 programme to add together justices to the court, Master Justice Charles Evans Hughes warned virtually "more judges to hear, more than judges to confer, more than judges to hash out, more judges to be convinced and to make up one's mind. The present number of justices is thought to be large plenty and so far as the prompt, adequate, and efficient conduct of the work of the Court is concerned."

Of the 54 state and territorial high courts, 29 have seven members. Only 10 accept ix, and none has more than 9. Judgeships on the 13 federal courts of appeals range from six to 29 with a median size of 13, simply those courts do most all their work in randomly selected three-estimate panels. Having three-justice panels decide cases for the unabridged Supreme Court would be unworkable because losing litigants would inevitably appeal a panel determination to the entire court, prompting satellite disputes about whether to rehear the case—and would probably violate Article Three's mandate for "one Supreme Court." The United Kingdom'southward 12-member Supreme Court works mainly in panels. The Canadian Supreme Court and Australian High Courtroom have nine and 7 judgeships, respectively.

Is the proposal to add seats to the Supreme Courtroom and to accept some justices appoint others constitutional? Is information technology practical?

Congress clearly has the constitutional authority to modify the size of the Supreme Court. And a statute prescribing some form of political party affiliation would withstand constitutional scrutiny. Section 251(a) of Championship 28 provides that no more than five of the nine U.S. International Trade Court judges may "be from the same political political party." The website of the Trade Court, though, makes no mention of its political party requirement, a reflection perhaps of a full general distaste for the idea.

Less debatable is whether the Constitution would countenance some justices appointing other justices, given Article II's mandate that the president, with Senate approval, appoint "Judges of the supreme Court." It leaves Congress the discretion to "vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper," in the president, the courts, or executive branch officials.

The five-five-five-member Courtroom plan would likely strike near legislators—ii professors' heavily footnoted pleas non withstanding—every bit Rube Goldberg judicial-machinery tinkering that would undermine lines of accountability for the justices selected by the other justices.

What would term limits achieve?

Justices have been serving longer terms. This table groups justices appointed since Congress settled on a nine-member Supreme Court.

Term limits and regularly recurring vacancies might tone downward the epic Supreme Court confirmation battles that have occurred roughly twice every eight years. Merely they might instead make knock-down, drag-outs a recurring part of the political mural. An election preceding the end of a swing justice's 18-year term could thrust the court into election twelvemonth battles more than intense than nosotros've already seen.

And what almost unanticipated effects? Would, for case, justices whose terms are nigh to terminate exist more willing to hear a case on which normally they might defer action to let the issue percolate in the courts of appeals?

The bigger question

That reasonable people are even debating these proposals speaks to the deposition of the federal judicial appointment procedure at all levels, a reject that has been building steam for several decades. The once near-ministerial task of appointing and confirming federal judges has stretched from one or 2 months into sometimes year-long ordeals, fifty-fifty for non-controversial nominees.

Both parties have undermined the guard rail that that one time pushed presidents and senators to seek judicial candidates within some wide mainstream of ideological boundaries, even assuasive for occasional outliers. Democrats killed the delay for most nominees, and Republicans finished it off for Supreme Court candidates and, to boot, ended the habitation-state senator (of either party) veto of circuit nominees that Republican senators exploited relentlessly to block Obama administration appointees.

Blame rising partisan polarization for the broken process. Merely Republicans should bear extra responsibility for their unprecedented stonewalling of President Obama's judicial nominees later Republicans took control of the Senate in 2015. GOP senators took hostage Justice Scalia'due south vacated seat and have used verbal contortions to justify confirming a nominee for whatever 2020 vacancy that might occur. That Senate in 2015-16 also confirmed far fewer appellate and trial court judges than did Senate majorities during divided government in previous administrations' final 2 years. That obstructionism ready the Trump administration's confirmation rush—peculiarly at the Supreme Court and court of appeals levels—seating 53 very conservative appellate judges for which the 2016 popular vote arguably provided no mandate.

Pack-the-court proposals that would usually seem bizarre are understandable in today's partisan climate. If the federal judiciary becomes a 21st-century version of the 1930s judiciary that thwarted a popular push for change, they may fifty-fifty get necessary.

Dig Deeper

Judicial appointments in Trump's first 3 years: Myths and realities

A December 24 presidential tweet boasted "187 new Federal Judges have been confirmed nether the Trump Administration, including 2 swell new United States Supreme Court Justices. We are shattering every record!" That boast has some truth but, to put it charitably, a lot of exaggeration. Compared to contempo previous administrations at this same early-fourth-twelvemonth point […]

Recess is over: Time to confirm judges

As information technology reconvenes after its summer recess, Congress faces the prospect of a partial government shutdown past calendar month'southward end. Federal courts are already partially shutdown. Of 852 federal district and circuit judgeships, 87 were vacant on September 6. Xxx-eight of the 49 awaiting nominees accept been waiting longer than has Judge Merrick Garland, who was […]

Pack the Court? Putting a pop imprint on the federal judiciary

In 1996, to caput off calls to impeach a life-tenured federal judge for ill-considered remarks about police officers, Chief Justice William Rehnquist cautioned that "judicial independence does non hateful that the country will be forever in sway to groups of non-elected judges." He recalled Franklin Roosevelt'south failed 1937 proposal to pack the Supreme Courtroom past […]

Source: https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/should-we-restructure-the-supreme-court/

Posted by: smitharing1997.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Can The Number Of Supreme Court Justices Be Changed"

Post a Comment